Hurricanes Becoming Less Frequent, More Costly

By Max Dorfman, Research Writer, Triple-I (04/08/2022)

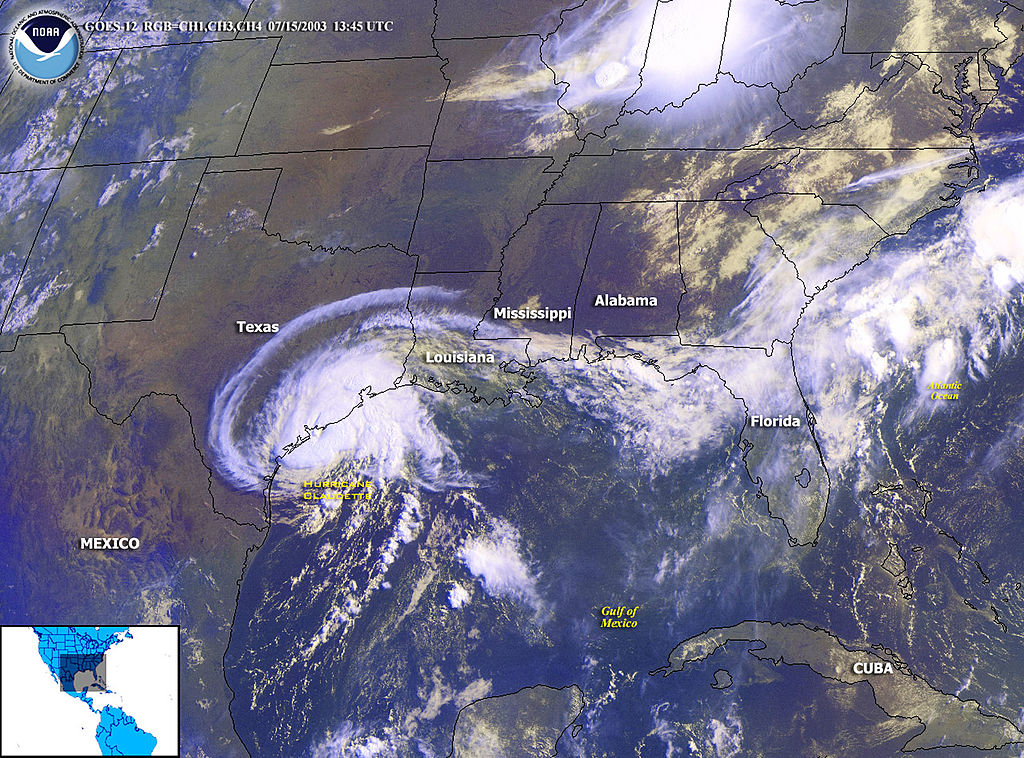

Hurricanes are becoming both less frequent and more powerful, according to a recent scientific paper.

Led in part by Triple-I non-resident scholar Dr. Phil Klotzbach, a research scientist in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University, the researchers uncovered that this trend has been propelled by a decrease in activity in the North Pacific from 1990 to 2021. The North Pacific is typically the most active of any global tropical cyclone basin.

Global tropical cyclone activity in this period has generated less accumulated cyclone energy, a metric that accounts for hurricane frequency, intensity, and duration. This trend has been driven by a more La Niña-like environment, a Pacific weather pattern during which winds blow strongly across the ocean from South America to Indonesia, with cold water rising to the surface.

This has, in turn, caused many of the powerful hurricanes to form in the Atlantic Ocean, while the frequency of Pacific storms – which historically have been more common – has declined. With increased populations in high-risk areas and the growing value of coastal assets, these storms have become even more destructive and costly.

To better understand this trend, we sat down with Dr. Klotzbach to discuss the paper and its implications.

Can you elaborate on the connection between weather patterns in the Pacific and Atlantic?

El Niño and La Niña both cause significant impacts on weather and climate patterns around the world. El Niño is warmer than normal water in the eastern and central tropical Pacific, while La Niña is colder than normal water in the same region.

In general, when El Niño occurs, it increases winds high up in the atmosphere in the Caribbean and tropical Atlantic, which then tear apart hurricanes. When La Niña occurs, the opposite set of conditions occur in the Caribbean and tropical Atlantic, favoring more active Atlantic hurricane seasons.

In the Pacific, the warmer waters associated with El Niño favor low-latitude formations of tropical cyclones. Such storms tend to last longer and reach higher intensities. During La Niña, low-latitude formation in the Pacific is typically suppressed.

We’ve known that the Atlantic has generally been more active since the mid-1990s, due to both a trend toward more La Niñas and fewer El Niños. But warmer waters in the Atlantic have been an even bigger driver of the increase there. Warmer Atlantic and Caribbean waters provide more fuel for developing hurricanes.

Is there any indication that Pacific storms will also grow more powerful in the future?

We don’t know for sure if the trend toward a more La Niña-like basic state will continue. If that trend were to reverse, we would expect to see an increase in the number of intense Pacific storms. Also, while storms in the Pacific have decreased, we did find an increase in the percentage of storms reaching Category 4-5 strength. This is consistent with what we would expect from climate change, where overall warmer ocean temperatures will likely lead to stronger hurricanes.

Does this shift in tropical global cyclone activity seem likely to continue?

Most climate models actually indicate that we should expect to see more El Niños and fewer La Niñas in the future. However, these models have biases that make their forecasts difficult to assess. At least for this year, it looks like we are likely to remain in either La Niña or neutral (neither El Niño nor La Niña) conditions. NOAA only gives a 10 percent chance of El Niño for the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season (August-October).

What are the short-term and long-term implications of these findings?

While climate change is projected to increase the intensity of hurricanes, the trend toward a La Niña-like basic state has helped to mask these increases over the past 30 or so years. To me, the critical question that needs to be answered is: Do we expect La Niñas to dominate with continued climate change, or will we transition back to an environment like we had in the early 1990s, when El Niños predominated?

Does this study suggest that there will be more damages?

We found a statistically significant increase in global damage. The big driver of this increase is likely growth in population and wealth along coastlines. As coastal populations are projected to keep increasing, we expect global damage from tropical cyclones to rise, as well. Improved building codes and better building practices could help mitigate some of this increase.